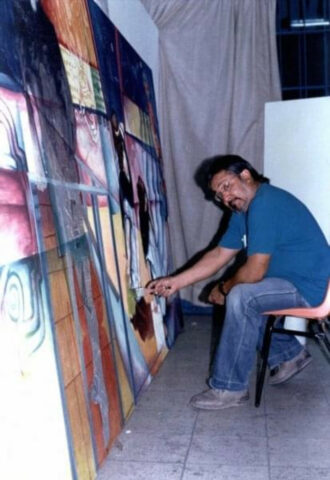

Raymond Michael Patlán had a profound impact on the country’s mural movement.

With roots in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood, the U.S. born muralist of Mexican descent got his introduction to the art world by watching his oldest sister and her classmates paint a mural on their public school wall. Later on, Patlán assisted a Mexican woman produce ceramics. The artistry of the work he witnessed moved him to pick up a pen and paper to illustrate scenes that touched him: images of the Mexican culture that dominated Pilsen in the 1960s and ’70s.

In 1966, he studied the art form in Mexico for several months, where he met renowned Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. In a 2016 interview with Jackie Serrato, a Chicago journalist for Gozamos.com, Patlán said: “What I learned from Siqueiros [was] that muralism isn’t like easel painting. It’s a whole environment. It’s an experience, a whole ambiente. It’s not just a painting on a wall.”

Patlán’s work painting murals in his beloved Chicago was delayed when he was drafted and shipped for a 13-month stint in Vietnam, where he served as a military correspondent for the Ninth Infantry Division that was stationed 30 miles northeast of Saigon. While there, Patlán convinced a chaplain to let him paint a mural in the back of a chapel at Camp Bearcat. Titled “The Wall of Brotherhood,” the 12 by 25-foot mural depicted the Vietnamese peoples’ daily struggles.

Shortly after returning to Chicago from his tour of duty, Patlán met fellow Chicagoan Mario Castillo, who is often credited as having created Pilsen’s first mural in 1968. Castillo’s influence moved Patlán to paint a mural in 1969 in the main sala of Casa Aztlan, a community service center in Pilsen. Patlán titled the mural “Hay Cultura en Nuestra Communidad” (“There is Culture in Our Community”).

The iconic mural featured Mexican symbols like skulls and flowers and paid tribute to historical social justice figures like Benito Juarez, Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa, Frida Kahlo, Father Miguel Hidalgo, Che Guevara and Cesar Chavez, serving as a reminder of the need for unity against oppression. Patlán also painted murals on the outside front walls of Casa Aztlan that showcased Mexican culture.

“Mario [Castillo] and Ray were the painters who launched the visual presence of art in Chicago in the 1960s,” said John Pitman Weber, a noted art historian and close friend of Patlán. “But Ray is credited for the explosion of visual art in Pilsen, both large and small, that gave the community identity.”

In 1971, Patlán, with the help of other artists, tried to paint a controversial mural in the Blue Island community. The mural, titled “The History of the Mexican American Worker” celebrated Mexican farmworkers, unionized labor and the growing latino community in Blue Island. It sparked threats against the artists, threats to bomb the building and it eventually led the city council to issue a ban on the mural, ordering for it to be painted white.

The mural was the subject of a precedent-setting legal case. When the city denied the artists a permit to paint, it claimed that the work constituted advertising in violation of a local zoning ordinance. Patlán and the artists sued the city. The American Civil Liberties Union took the case to the Illinois Supreme Court, arguing the First Amendment right of the artist’s to freedom of speech had been violated. The judge ruled in the artists’ favor. By 1974, the mural was completed.

Pilsen was hit hard by gentrification in the early 2000’s, after more white and middle-class people started to move in. Companies began to buy up property to build luxury high-rises, increasing rents in the historically working-class neighborhood. By 2010, the Latinx population in Pilsen declined by 26 percent.

In 2013, financial hardship forced Casa Aztlán to close its doors. When a developer took it over in 2015 to create an apartment building, Patlán’s outside mural was painted over in gray paint, igniting fierce community opposition. In response to the backlash, the developer asked Patlán to have the mural repainted. Patlán agreed, on the condition that he would repaint the mural based on what residents wanted to see. The project was completed in 2017.

Patlán’s formal training as an artist began at the Art Institute of Chicago and later at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico. In 1975, Patlán left Chicago to relocate to San Francisco for a possible teaching position in the Chicano Studies program at U.C. Berkeley. The course focused on mural art and photography. However, the job offer was contingent on first getting a Bachelor of Arts degree. Being only a few units shy of getting the B.A., Patlán quickly enrolled at Chicago State University and got the degree. Later, he would earn a Master of Fine Arts at California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland.

In 1983, Patlán became the founding director of Creativity Explored of San Francisco, a studio for artists with developmental disabilities, serving in that role for 15 years.

Patlán’s most significant imprint in San Francisco was as co-founder, along with Patricia Rodriguez, of the PLACA project in the Mission District from 1982 to 1984. The volunteer effort led to the creation of 26 murals in Balmy Alley. Patlán painted two murals and guided some 40 artists in producing the others. The project grew out of support for the Central American resistance movement in the 80s and against U.S. intervention in Central America. The artists also wanted to show solidarity with the growing Central American population in the Mission.

At least three to four murals from that period still exist. As murals gave way to weather and reconstruction by new owners, new artists contributed new murals, and themes expanded to include other freedom struggles, AIDS, and gentrification. The murals stretch the length of Balmy thanks to the willingness of the property owners to allow their garage wall space to be painted.

As a resident of Balmy Alley, Patlán kept his eye on the murals, and protected them as best he could. As a result, he was christened the Mayor of Balmy Alley.

During his lifetime, Patlán was responsible for over 100 murals. There are 62 of them in the San Francisco Bay Area, and 12 in Chicago. Internationally, he also painted two murals in Mexico, one in Vietnam and one in England.

Patlán was born on September 4, 1946, in Chicago to parents Candido and Remedios (Gonzales) Patlán. He died at the age of 76 in Oakland on April 15, 2024. Ray Michael Patlán is survived by sisters Cecelia Patlán, and Sally Chico, as well as numerous nieces and nephews. Two other sisters, Anne Bernal and Gloria Cerda, are no longer living.

To celebrate the life of the legendary muralist Raymond Michael Patlán, there will be a public gathering in the Mission District’s Balmy Alley on Sunday, June 23 from 4-6pm. For more details, please email patlanmemorial@gmail.com.

¡Raymond Michael Patlán, Presente!